Multiple Measures for College Placement: GOod Theory, Poor Implementation

Alexandros M. Goudas (Working Paper No. 6) April 2017 (Updated May 2019)

A pattern is developing in the recent community college reform movements sweeping the nation. Researchers publish studies claiming a certain component of higher education is not working well, and in these studies they propose data-based solutions. Then due to various reasons, institutions implement those solutions in ways different from the original recommendations. Sometimes these variations differ drastically from the recommendations backed by research.

One can clearly see this with the corequisite reform movement. Guided pathways is also being implemented in vastly different ways, some of which are antithetical (Scrivener et al., 2018) to the authors’ recommendations (Bailey et al., 2015). The most recent example of this pattern, however, has to do with college placement. A good theory for reforming placement in college—the use of multiple measures—has largely been implemented improperly, and much of the fault lies with the researchers who have studied the problem and made recommendations for change. Indeed, many of their proposed reforms contradict their own initial research.

This improper application of research may negatively affect tens of thousands of students placing into remedial and college-level courses across the nation. In fact, anecdotal evidence from various states suggests significant damage has already been done. To prevent the problem from getting worse, the multiple measures movement should be understood more fully. Practitioners and policymakers need to know what exactly multiple measures are, what the data say they can do to increase outcomes, and how they should be implemented thoughtfully. This needs to be addressed before more at-risk students are improperly placed or excluded due to the use of variations of multiple measures which are not based on research.

Traditional Placement in Community Colleges

Before discussing the events leading up to this misapplication of research, it would be helpful to understand what placement measures currently exist and how they have been used in colleges across the nation traditionally. Typically most students place into college-level courses in community colleges and open admissions universities in the following manner: If students have high enough ACT or SAT scores, colleges typically allow students to enroll in college-level gateway courses. If they do not score high enough or do not even have ACT or SAT scores, then the majority are usually required to take a placement examination.

This placement exam has either been Accuplacer or Compass, but most institutions now use Accuplacer or their own test because Compass was discontinued at the end of 2016, largely due to the recent research on placement tests. While Compass was a product of ACT, Accuplacer is produced by College Board, the same testing company which created the SAT. These placement tests are similar to their respective ACT and SAT tests, but they are shorter, more focused, and are specifically designed to diagnose whether students will be successful in writing, reading, and math gateway courses. They have a level of predictive validity based on each organization’s research into their test’s scores and students’ subsequent grades in respective college-level courses (Westrick & Allen, 2014). They each recommend cut scores, above which students qualify for college-level courses, and below which, students qualify for remedial courses.

The Community College Research Center Weighed In on Placement

In February 2012, Community College Research Center (CCRC) researchers Scott-Clayton, Belfield, and Crosta posted two working papers simultaneously. Both papers summarized the researchers’ analyses on the predictive validity of Compass and Accuplacer using anonymized urban and state data. They both concluded that as stand-alone tests, both Compass and Accuplacer have relatively low predictive validity. They also found that cumulative high school grade point average (HSGPA) is a slightly better stand-alone predictive measure. However, most importantly, they found that when they combined these two measures together—a placement test score and a student’s HSGPA—to form another placement score, that measure was even more predictive of student success in college-level courses. Scott-Clayton (2012) went further and combined up to four different measures to make a “rich predictive placement algorithm” that predicted student performance even better than the combination of two or three measures (p. 33).

Their combined press release boasted such figures as a 50% reduction of over- and under-placement from one of their studies, though the other study only found a 10-15% reduction. News organizations like Inside Higher Ed (IHE) and others latched on to the studies and the press release, and they immediately wrote articles summarizing the research. From these papers and the subsequent news reports, an idea was planted in the minds of education leaders: using HSGPA alone to place students would increase student performance outcomes. For instance, Paul Fain of IHE, in an article entitled “Standardized Tests That Fail,” (2012) quoted Belfield and Crosta (2012): “‘Information on a student’s high school transcript could complement or substitute for that student’s placement test scores,’ according to the report. ‘This would lead to a faster and more successful progression through college'” (para. 13).

With funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, which allowed them to study the issue from 2009-2013, the CCRC began speaking and writing about the use of HSGPA extensively across the nation shortly after the papers were released. Once administrators, legislators, and other college leaders heard from reputable researchers that an easier and cheaper method would do a better job at placing students, they rushed to adopt the change. As one example, the CCRC had an agreement with the North Carolina Community College System (2016) to work together to improve outcomes. Based on CCRC research, beginning in Fall 2013 and continuing over approximately three years (there was a delay recommended to the State Board of NC), the entire state of North Carolina phased in a multiple measures mandate that places students who have a cumulative HSGPA of 2.6 or higher in college-level courses (p. 1), bypassing remedial courses regardless of whether students demonstrate proficiency in those course outcomes. The community college state system of Indiana, called Ivy Tech, has followed suit and set their college-level entrance bar at 2.6 HSGPA as well (Ivy Tech Community College, n.d.). Others are beginning to implement similar versions of these two states’ placement systems.

Practitioners have since become concerned about two questions: If the goal was supposed to be the use of “multiple measures,” why is the new recommendation to use HSGPA alone as the primary placement metric? Second, if HSGPA is to be the new measure, why is the bar set at 2.6? The answers to these questions have to do with the evolution of the original multiple measures recommendation into what should be called the “multiple single measures” reform, which is currently being promoted by the CCRC and others.

Originally, both Scott-Clayton (2012) and Belfield and Crosta (2012) conducted regression studies correlating placement tests and HSGPA with performance in college courses. Using theoretical regression estimates, they found that cumulative HSGPA does a slightly better job explaining student outcomes in college, most likely because, as Belfield and Crosta put it, “In contrast to a single-value placement test score, high school transcripts may yield a wealth of information. Potentially, they can reveal not only cognitive competence but also student effort and college-level readiness [i.e., noncognitives]” (p. 3).

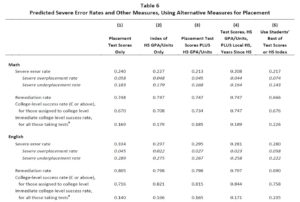

More than this, however, they also found that combining HSGPA and a placement test made their predictions slightly better. Scott-Clayton (2012), referring to Table 6 (p. 31) (table shown below), stated that “the use of multiple measures can enable a system to reduce severe placement errors and improve college-level success rates, while keeping the remediation rate unchanged—or to reduce remediation rates without any adverse consequences” (p. 36). As one can see in the table, when placement test scores are combined with HSGPA, the rate of severe misplacement, meaning the rate at which students are misplaced in remediation or college-level courses, goes down.

In column 1 are the severe placement error rates, remediation rates, and college success rates when only looking at placement tests. In column 2 are the severe error rates and other metrics when using HSGPA alone, and those rates are slightly lower compared to placement tests. Column 3 shows how error rates decline even more when placement test scores and HSGPA are combined. Finally, column 4 above shows how they decline further if even more measures are added to form a multiple measure of more than two metrics. From this study and Belfield and Crosta’s (2012) similar study, then, the term “multiple measures” became popularized.

Mixed Measures CHanged into Multiple Single Measures

In 2012, Scott-Clayton, Crosta, and Belfield (2012, 2014) combined their efforts and began the process of publishing a paper in the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). In this paper, they recommend that “using high school transcript information—either instead of or in addition to test scores—could significantly reduce the prevalence of assignment errors” (abstract). This is the beginning of the shift from “multiple measures” to “multiple single measures.” They started recommending that either multiple measures (i.e., a placement test in combination with HSGPA), or only HSGPA alone, should be used to place students into or out of remediation.

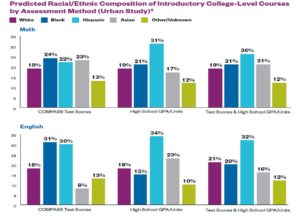

However, due to a troubling problem they found when they analyzed the use of HSGPA alone as a placement measure, the CCRC had to modify their recommendation for HSGPA as a single measure. In 2015, the CCRC released a summary of their placement research (Scott-Clayton & Stacey, 2015). In this summary, they showed that using HSGPA alone would have a negative effect on certain subpopulations in particular course placements, namely African-Americans and Asians. Below is a chart they include to help institutions understand the positive and negative effects of using HSGPA alone as a placement measure.

According to the Scott-Clayton and Stacey (2015) chart, using Compass as a sole placement tool places 24% of Black students in college-level math courses, but if HSGPA alone is used instead, it only places 21% of Black students into college-level math courses (p. 3). Worse yet, for Blacks being placed into English, only 15% place into college-level courses with HSGPA alone. This is in stark contrast to the 31% of Blacks who place into college-level English courses with placement tests. Using HSGPA reduces Black students’ college-level placement by more than half in English. A similar problem exists for Asians testing into college-level courses using HSGPA versus placement tests in math: 23% of Asians place into college-level math courses with a placement test, whereas only 17% of Asians place into college-level courses with HSGPA alone. These data pose a significant problem for the CCRC researchers and institutions who promote and use HSGPA as a sole measure for placement.

Interestingly, the authors’ response to the problem with minority subgroups was to recommend two actions. First, they recommended that institutions choose to employ either placement tests or HSGPA. Scott-Clayton and Stacey (2015), in the first of two “research tool” documents designed to help institutions improve placement, stated, “One way to avoid differential impacts on subgroups would be to allow students to test out of remediation based on either test scores or high school achievement” (p. 3). They imply that institutions should use placement tests for some groups and HSGPA for others, whichever moves more students into college-level courses.

Second and more importantly, they recommend that institutions lower the recommended cumulative HSGPA to a level at which most students would place into college-level courses. In a companion paper produced by Belfield (2015), the second “research tool” document designed to assist institutions in improving placement, the CCRC described how to lower HSGPA for placement into and out of remedial courses:

A simple decision rule that colleges could use instead of administering a traditional entry assessment would be to assign students to developmental education if their high school grade point average (GPA) is below a threshold (such as 2.7 or 3.0). (p. 2)

Aside from trying to avoid negative effects for minorities with the use of HSGPA, perhaps another reason why the CCRC ended up recommending the number 2.6 as a cutoff is because Belfield (2015) stated that the “typical community college student has a high school GPA of around 2.7 (B minus)” (p. 5). Since placement tests typically assign students to college-level courses if they are around the 50th percentile or higher, perhaps the CCRC decided to use the average of HSGPA of community college students to arrive at a similar cutoff.

Nevertheless, it appears that the main reason the CCRC made the recommendation to the state of North Carolina in 2013 to move their HSGPA placement level down to 2.6 was to address the negative effects of HSGPA placement on minorities. Regardless of the reasons, however, the end result is that what originally started as “multiple measures” ultimately morphed into “multiple single measures,” starting with the recommendation by the CCRC for institutions to allow students to have a choice between placement test scores or HSGPA.

Compounding the problem, what states and various institutions did with this information was to simply add a HSGPA cutoff to their existing means by which to place students into college-level courses. Ivy Tech’s website on placement is the clearest example of this. Aside from transferred credits, they have five different measures students can choose from to place into college-level courses: ACT, SAT, PSAT, Accuplacer, or HSGPA. Below is an older but simpler version of their current website which outlines the various ways for students to place into college-level courses.

When students are given the option to qualify for college-level courses using five options, it lowers the college-level cutoff bar overall. It does this is by allowing some students to place into college courses with one metric, others to place with another metric, and even more with a third, fourth, or fifth metric. The more metrics an institution provides as options, the more students will place into college-level courses. It may in fact have been the intent of the CCRC and others to recommend the placement of as many students into college-level courses as possible since the they believe remediation is ineffective and have been repeating this statement for years.

In support of this assertion, Elisabeth Barnett, a lead researcher at the CCRC, commented on multiple measures in an Inside Higher Ed (IHE) article (Smith, 2016). Barnett implied that avoiding remediation is the most important goal for placement: “’Any single test isn’t going to be predictive [of student success], but the advantage of having other measures is you have various ways to get placed out of developmental education'” (para. 3). While Barnett correctly noted that a single test is not very predictive of success, she failed to note that the use of “other measures” should not be much more predictive since they are all single measures. Barnett did not appear to reinforce the original research the CCRC created in 2012 showing that the use of actual “multiple measures,” meaning combined measures, is the best recommendation. Barnett’s recommendation was instead promoting the use of HSGPA alone because she argued that it is not a single measure, but instead “a compilation of course grades over time” (para. 17).

Even if Barnett is referring to the research that shows HSGPA alone is a slightly better predictor of success compared to placement tests, her statement still contradicted claims from her and Reddy’s working paper highlighted in the IHE article. This working paper is the culmination of CCRC multiple measures research, and it can be found in a Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness (CAPR) document released in February of 2017 (Barnett & Reddy, 2017). (A note for readers on these organizations: CAPR is a research organization headed by Thomas Bailey and is an offshoot of the CCRC. The Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment (CAPSEE) and the National Center for Postsecondary Research (NCPR) are two other offshoot research organizations; all four, including the CCRC, were headed by Bailey until he became President of Teachers College, and they often share the same researchers, themes, topics, and conclusions.)

What contradicted Barnett’s statement in the IHE article is Barnett and Reddy’s (2017) definition of what “multiple measures” are: “We define multiple-measures placement as a system that combines two or more measures to place students into appropriate courses and/or supports” (pp. 8-9). Using this definition, they continued on to outline five strategies for institutions to be able to combine measures for more appropriate placement.

In spite of setting the goal of utilizing actual “multiple-measures placement,” however, Barnett and Reddy’s (2017) first recommendation is a waiver system, which essentially promotes the use of a single measure:

In a waiver system, one or more criteria are used to waive placement testing requirements and allow students to place directly into college-level courses. At some colleges, students with a specified high school GPA or standardized test score are exempt from placement testing. In Ohio, legislation requires that students be considered college-ready (or ‘remediation-free’) if they meet pre-defined scores on widely used assessments such as the ACT, SAT, and ACCUPLACER, or less commonly administered assessments, such as ALEKS, Place U., and MapleSoft T.A. (p. 9)

The system of six single measures that Barnett and Reddy (2017) described from Ohio is the same as the systems being used in North Carolina and Indiana. Again, however, employing “one or more” criteria as a waiver system does not qualify as a true “multiple measure” according to their own definition. What Barnett and Reddy are actively promoting, then, is the use of “multiple single measures.” This fundamentally serves to reduce placement into remediation and to put as many students as possible into college-level courses, and it not actually based on hard data because little research has been done tracking the outcomes of students who place into college-level courses with HSGPAs as low as 2.6–2.9. One of the only follow-up reports looking into the effects of lowering placement to 2.6 was conducted in numerous community colleges in NC. Students who placed into college-level courses between 2.6–3.0 did not fare well, so these institutions put various supports in place (Achieving the Dream, n.d.; Clery et al., 2017). Additionally, since their waiver system recommendation is the first on the list, it must be assumed that it is the most important recommendation they have for the implementation of multiple measures.

Barnett and Reddy’s (2017) second, third, and fourth recommendations are indeed multiple measures (decision bands, placement formula, and decision rules), but options two and four are essentially the same process. Therefore, they are recommending only two actual multiple measures. The fifth and last recommendation they make is called “Directed Self-Placement.” This is their description of the option:

With directed self-placement, students may be permitted to place themselves into the course level of choice, usually informed by the results of placement testing, a review of their high school performance, and/or information about college-level expectations in math and English. Florida has instituted this policy across its colleges based on legislation passed in 2013. Early descriptive data from Florida indicate that directed self-placement leads to much higher enrollment rates in introductory college-level courses in English and math but lower pass rates for these courses. However, the sheer number of students passing a gateway course has increased over time (Hu et al., 2016). (p. 10)

The use of “and/or” makes this fifth option yet another “multiple single measure.” Even worse, this recommendation for allowing students to choose to take college-level courses, using Florida as an example, is in fact the promotion of the employment of no placement measures. Promoting the elimination of all placement measures is reminiscent of the “right to fail” sentiment that many in higher education currently hold. This fifth option of student choice further confuses the problem since it should be assumed that institutions will read this CAPR paper and view the recommendation of optional remediation as a multiple measure because it is placed under the “five approaches that permit measures to be combined for placement purposes” (Barnett & Reddy, 2017, p. 9). Based on the wide variations of “multiple single measures” placement occurring in many states, one can assume that most policymakers are not reading the paper carefully.

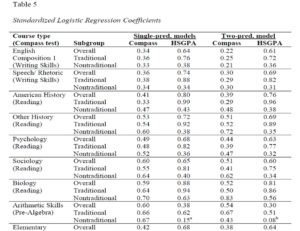

Aside from the unintended consequence of harming certain minorities’ placement into college-level courses, other subgroups may be harmed as well with the use of HSGPA. In an ACT research report from 2014 on Compass and HSGPA placement validity, Westrick and Allen found that in many subjects, the use of HSGPA does not predict nontraditional students’ performance as well as placement tests do. On page 15 in Table 5 (see below), these researchers compared the regression coefficients of Compass versus HSGPA for 12 college courses. In 8 of the 12 courses, the placement test performed as well as or better than HSGPA for nontraditional students. The surprising part of this finding is that they defined “nontraditional” as age 20 or higher. In most literature, nontraditional students are defined as age 25 or higher. What this means is that the use of HSGPA alone may harm the placement of a quarter to a third, or more, of incoming students simply because they are age 20 or above.

Other potential problems with the practical use of HSGPA for placement include the fact that many students do not have access to, nor may they submit their HSGPA to postsecondary institutions. It likely has to do with age, access to resources, limited time, and the knowledge of how the K-12 and college systems work. Indeed, Scott-Clayton (2012) and Belfield and Crosta (2012) both note that approximately 30 to 50% of their samples did not even have a HSGPA to analyze, and most of the students whose HSGPAs were used in the studies were just out of high school (Belfield & Crosta, 2012, pp. 7-8; Scott-Clayton, 2012, p. 35).

Similarly, the National Center for Education Statistics reports that anywhere from about 15 to 25% of incoming 2- and 4-year college students have missing HSGPA data (Chen, 2016, p. 13). Even a recent study by Barnett et al. (2018) attempting to improve placement using actual mixed measures showed that approximately 60% of students had missing HSGPA (p. 64). These missing data may be undermining our ability to understand how HSGPA affects college placement, and it also may reduce the effectiveness of using HSGPA as a placement measure. It may end up simply benefiting those who are already well prepared.

On a positive note, the CCRC and related organizations recently decided to invest in a true mixed measure experiment to see whether mixed measures could be practical and improve placement. Barnett et al. (2018) conducted a randomized controlled trial, a relatively rare design in postsecondary research, using students at five State University of New York community colleges to place them with a mixed measure and track their success in college. Even though the study revealed numerous problems, such as the fact that about 60% of students in the sample had missing HSGPA (p. 64) and the fact that employing true mixed measures costs a great deal of time and money (p. iv), their preliminary results showed that fewer students are being misplaced. Gateway completion rates after one semester of analysis indicated slightly higher numbers for the program group. This is an ongoing study, and several semesters’ worth of data will be released in a later report.

The Goal of Multiple Measures

The entire premise of the multiple measures movement, as stated in Fain’s (2012) article, is founded on the idea that putting more students into college-level courses will equal faster and higher completion rates. Unfortunately, there is no evidence of this from any current research. Research from corequisites, which essentially puts more remedial students into college-level courses with additional support, has shown no improvement in graduation rates. In fact, the only moderately rigorous research on corequisites revealed that the model caused a statistically significant decrease in certificate attainment and lower outcomes for nonremedial students, all of which counteracts the limited and temporary positive increases for corequisite remedial students.

Moreover, data from Florida, which Barnett and Reddy (2017) cited, showed no increase in graduation rates as a result of more students enrolling in college-level courses. In fact, as they stated above, it leads to slightly more students passing college-level courses overall, yet it also leads to a many more students failing those courses as well. One can conclude from the experiment in Florida and from other recent reforms that if at-risk students are put into college-level courses at a higher rate, especially without support, a few will do well, but many more will fail college-level courses.

Finally, it is of utmost importance to understand that while HSGPA may do a better job at predicting success in college (i.e., graduation), it may not do well demonstrating whether a student can understand and complete college-level material. Millions of high school students graduating this year will have a cumulative HSGPA of 2.6 or higher but may not have the skills or knowledge to understand concepts from and perform well in college-level English and math. The assumption is that since these students were able to complete high school with a GPA near the community college average or higher, they will also be likely to complete college-level English and math. This assumption confuses apples with oranges. Common sense says that if a student does not understand fundamental concepts, especially in a tiered subject such as math, they will not be able to perform well with higher-level material, regardless of their HSGPA. This is yet another reason why actual “multiple measures” should be employed rather than “multiple single measures.”

Furthermore, if it is accepted that HSGPAs include noncognitive measurements, as Belfield and Crosta (2012) implied, and it is accepted that higher HSGPAs reflect better noncognitives, then does that mean institutions should remediate for noncognitives? In other words, tens of thousands of students will now be placed into remedial courses because their HSGPA is too low. If their HSGPA is low because they had trouble getting to class, being organized, or completing or turning in homework, will preparation for college-level English and math concepts and skills improve their probability of graduating? Conversely, if a student’s HSGPA is 2.8 because they showed up for every class and turned in all their homework for four straight years in high school, yet they still struggle with basic English and math, will they necessarily be successful with college-level gateway course content?

If institutions choose to place students into remedial courses using noncognitive measures, then those remedial courses must also address those noncognitives. If cognitive measures are used for placement, as they were with Compass and are with Accuplacer and other subject-level tests, then the courses students are placed into should address those content deficiencies. Moreover, if cognitive and noncognitive measures are combined, courses should reflect those measures. If institutions place students into courses with metrics different than what will be addressed in those courses, they may set up both remedial and nonremedial students for failure.

As with anything, the more is invested in placement and the more high-quality measures are used, the better placement will be. If, perhaps, students were required to write an entire essay as a placement measure, or students were required to take a division-approved math placement test, in addition to their HSGPA and Accuplacer score, then intake officials at colleges and universities would have a much clearer picture about their abilities. Even better would be to have these students sit down and talk to a counselor about their life situations, their aspirations, and their potential setbacks. Saxon and Morante (2014) outlined best practices regarding holistic placement procedures, namely mandatory advising for new students, as one key example, with advisers having a lower ratio of students to accommodate the increase in time which would be required (p. 28). Even Bailey et al. (2015), the authors of the book on the guided pathways model, spent a great deal of time arguing for increased resources for counseling and intake.

The combination of all these metrics could result in a true “multiple measure” placement that would best fit individual students. Using a thoughtful, well-supported and holistic system for admissions and placement will always outperform one, two, or five “multiple single measures,” yet this takes a significant investment of time, staffing, software, and money. The return on that investment, however, may be larger than people think.

References

Achieving the Dream. (n.d.). Multiple measures for placement.

Bailey, T. R., Jaggars, S. S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: A clearer path to student success. Harvard Press.

Barnett, E., Bergman, P., Kopko, E., Reddy, V., Belfield, C., Roy, S., & Cullinan, D. (2018). Multiple measures placement using data analytics: An implementation and early impacts report. Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/multiple-measures-placement-using-data-analytics.pdf

Barnett, E. A., & Reddy, V. (2017). College placement strategies: Evolving considerations and practices (CAPR Working Paper). Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/college-placement-strategies-evolving-considerations-practices.pdf

Belfield, C. R. (2015). Improving assessment and placement at your college: A tool for institutional researchers. Community College Research Center, Columbia University, Teachers College. http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/improving-assessment-placement-institutional-research.pdf

Belfield. C. R., & Crosta, P. M. (2012). Predicting success in college: The importance of placement tests and high school transcripts (CCRC Working Paper No. 42). Community College Research Center, Columbia University, Teachers College. http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/predicting-success-placement-tests-transcripts.pdf

Chen, X. (2016). Remedial Coursetaking at U.S. Public 2- and 4-Year Institutions: Scope, Experiences, and Outcomes (NCES 2016-405). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016405.pdf

Clery, S., Munn, B., & Howard, M. (2017). North Carolina multiple measures implementation and outcomes study: Final report. Coffey Consulting, LLC. http://www.coffeyconsultingllc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/NC-Multiple-Measures_FINAL_Rev-1_29June2017.pdf

Fain, P. (2012, February 29). Standardized tests that fail. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/02/29/too-many-community-college-students-are-placing-remedial-classes-studies-find

Ivy Tech Community College. (n.d.). Assessment for course placement. https://www.ivytech.edu/admissions/assessment-for-course-placement/

North Carolina Community College System. (2016). NCCCS policy using high school transcript GPA and/or standardized test scores for placement (multiple measures for placement). https://www.nccommunitycolleges.edu/sites/default/files/basic-pages/student-services/multiple_measures_of_placement_revised_august_2016.pdf

Saxon, D. P., & Morante, E. A. (2014). Effective student assessment and placement: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of Developmental Education, 37(3), 24-31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24614032

Scott-Clayton, J. (2012). Do high-stakes placement exams predict college success? (CCRC Working Paper No. 41). Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/high-stakes-predict-success.pdf

Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P. M., & Belfield, C. R. (2012). Improving the targeting of treatment: Evidence from college remediation (NBER Working Paper No. 18457). National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w18457.pdf

Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P. M., & Belfield, C. R. (2014). Improving the targeting of treatment: Evidence from college remediation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(3), 371–393. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713517935

Scott-Clayton, J., & Stacey, G. W. (2015). Improving the accuracy of remedial placement. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/improving-accuracy-remedial-placement.pdf

Scrivener, S., Gupta, H., Weiss, M. J., Cohen, B., Cormier, M. S., & Brathwaite, J. (2018). Becoming college ready: Early findings from a CUNY Start evaluation. MDRC. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/CUNY_START_Interim_Report_FINAL_0.pdf

Smith, A. A. (2016, May 26). Determining a student’s place. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/05/26/growing-number-community-colleges-use-multiple-measures-place-students

Westrick, P. A., & Allen, J. (2014). Validity evidence for ACT Compass placement tests. ACT Research Report Series. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED546849.pdf