Students or Customers? The Term Makes a Difference

Alexandros M. Goudas (Working Paper No. 4) February 2017

The corporatization of education has been rapidly expanding in the US for about twenty years now. It started with charter schools in the early 1990s, and it gained traction in higher education in the wake of massive state cuts to colleges and universities over the past ten years. States are still not funding higher education as much as they did before the recession (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2015, p. 4). Overall funding for students in higher education has been trending downward since 2000. The Pew Center has good data on the downward trends of higher education funding from both federal and state sources over the past two decades (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2019).

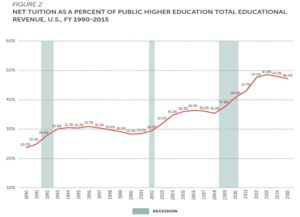

All these cuts have caused colleges and universities to raise tuition substantially in order to cover costs (Webber, 2016). The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (2015) generates an annual report on higher education funding in which Figure 2 below can be found (p. 22). As one can clearly see, total higher education revenue from tuition used to be about 25% in 1990, whereas it rose to near 50% by 2015. The Great Recession caused much of the most recent increase.

Aside from raising tuition, most institutions of higher education are also engaging in for-profit business tactics to cut costs and generate revenue (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2009). Their boards increasingly hire presidents and provosts who are called CEOs and who have corporate, for-profit executive experience, and then they pay them like CEOs. In fact, the average base pay of community college presidents is already $225,000 (Flaherty, 2016), which, along with benefits such as travel, car, residence, and healthcare, nearly puts them in the top 1% of earners. President CEOs may even groom their governing boards with CEO-board manuals, conferences, and meals (Koch, 2018). Many board members come from the business community as well, so board members and CEO college presidents may form very close ties.

Boards and trustees will often support a new corporate-minded CEO in their attempt to structure a university or college like a business. Among the numerous other typical for-profit decisions a company might make, many new education leaders are engaging in one or more of the following, even though many of these decisions do not actually improve outcomes: cutting full-time faculty; cutting release time for faculty; consolidating roles in mid-level management; cutting budgets for professional development; increasing spending on marketing; obsessing over enrollment and retention above all else; and increasing the use of adjuncts, increasing student-teacher ratios, and increasing the use of fully online instruction, all three of which, according to Bailey et al. (2015) (p. 174) and the Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment (CAPSEE), most likely harm completion and quality.

Boards and trustees will often support a new corporate-minded CEO in their attempt to structure a university or college like a business. Among the numerous other typical for-profit decisions a company might make, many new education leaders are engaging in one or more of the following, even though many of these decisions do not actually improve outcomes: cutting full-time faculty; cutting release time for faculty; consolidating roles in mid-level management; cutting budgets for professional development; increasing spending on marketing; obsessing over enrollment and retention above all else; and increasing the use of adjuncts, increasing student-teacher ratios, and increasing the use of fully online instruction, all three of which, according to Bailey et al. (2015) (p. 174) and the Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment (CAPSEE), most likely harm completion and quality.

All this has led to a shift in language: students have now become customers. As we can learn from politics, the terminology we use to describe people or issues can dramatically change the decisions we make about them. Perhaps the most well-known example in politics involves immigration. What should we call immigrants in the US who do not have residence documentation? Unauthorized workers, undocumented immigrants, illegal immigrants, illegal aliens, aliens, or illegals? It gets far more complicated than this. In fact, a Fordham Law Review article (Cunningham-Parmeter, 2011) has illustrated just how much the field of cognitive linguistics has contributed to our understanding of the impact of language on law and policy.

An even better but little-known example of the effect of nomenclature on policy involves the story of death panels, a term one may recall from 2009. NPR’s Planet Money (“Episode 521,” 2014) podcast first detailed this fascinating story, but an overview of it can be read here as well. Essentially, a hospital in La Crosse, Wisconsin found that it could reduce the total cost of healthcare spending by about a quarter if staff were able to convince most residents to sign end-of-life documents, such as living wills. The hospital targeted these documents because approximately 25% of healthcare spending is used in the final year of life, mostly by prolonging people’s lives when no one knows whether they wish their lives to be prolonged. Through a culture change in the small town, brought about mainly by nurses educating patients, almost every resident voluntarily signed one (96% in La Crosse versus 50% overall in the U.S.). In fact, it became a regular topic of conversation among townspeople, and they believe it has helped their lives overall.

As a result, La Crosse became the city with the lowest Medicare spending per person in the U.S. (“Episode 521,” 2014). The doctor who started this program attempted to devise a national model to reduce total spending on Medicare, but because of the intervention of Sarah Palin and other politicians, this idea became dubbed death panels. The public became concerned, and thus a means by which the nation could have voluntarily and easily decreased Medicare spending by billions of dollars was removed from the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (Obamacare). It was a misrepresentation of a very simple, unintrusive, and effective method to increase the quality of people’s lives and save a great deal of money.

Likewise, the use of the term customers for students will have real-life consequences. Before discussing those consequences, however, the reason why the use of the term can have such a negative impact on education needs to be fully understood.

It has to do with a set of accepted societal norms that an institution automatically agrees to when its leaders decide to call students customers. When a student becomes a customer, this denotes a certain relationship the institution will have with that customer. The institution then becomes a business that wants to attract and retain the customer. The end goal for the business is to generate profit and have high performance marks, and the end goal for the customer is to get what they want, in this case, grades and a degree. The relationship is often characterized as the commercial model.

This business-customer model works very well for most products and some services in the capitalistic free-market economy we have in the US. Take Amazon, for example. They compete for customers by attempting to offer cheaper products compared to Target or Walmart. If a product is cheaper at one site or store, customers win, and the business that is most able to juggle spending, revenue, and low prices will ultimately win as well. Of course, this system has unintended consequences for employees, customers, and communities, but strictly looking at the commercial model in terms of cost per product, the self-interest-based competition for goods and basic services can often create a win-win for both parties. It is the heart of capitalism.

However, the commercial model does not quite work the same way in realms such as education, healthcare, and the prison system. When for-profit practices are applied in these areas, there are consequences for customers that are not readily apparent. It is well known that companies will cut corners to save money and increase profits, but it can become dangerous for customers when those customers are, for example, prison inmates. To illustrate, in Michigan, state officials decided to privatize parts of the prison system. Aramark, a for-profit company with approximately$14 billion in annual revenue, was hired for a three-year contract to provide meal and other services for Michigan prison inmates. The company cut corners in hiring and management, and it resulted in problems with food quality, sexual relations between employees and inmates, and drug smuggling in some of these prisons (Egan, 2016).

Additionally, a recent national study of federal prisons shows that privately run prisons have greater problems with security and safety, while at the same time do not save any money for the federal government, which was the number one reason these contract prisons were created. Incidentally, the federal government has been moving to end the private federal prison system because it is clearly not improving outcomes.

In education, one can find similar problems with the quality of services of for-profit institutions and nonprofit institutions that resemble for-profits. An excellent book examining the effects of privatizing education is called Education and the Commercial Mindset by Samuel E. Abrams (2016). The book begins by chronicling the charter movement and highlighting the various failures of several education management organizations (EMOs), such as Behavioral Research Laboratories in the 1970s, Educational Alternatives Inc. in the 1990s, and Edison Schools Inc. in the late 1990s and 2000s (pp. 8–9). They all attempted to improve K-12 education in the U.S. by using the commercial model. However, at no time in the past forty years has a for-profit model in education been able to improve student outcomes and make money simultaneously. More often than not, they even fail to raise student performance.

In education, one can find similar problems with the quality of services of for-profit institutions and nonprofit institutions that resemble for-profits. An excellent book examining the effects of privatizing education is called Education and the Commercial Mindset by Samuel E. Abrams (2016). The book begins by chronicling the charter movement and highlighting the various failures of several education management organizations (EMOs), such as Behavioral Research Laboratories in the 1970s, Educational Alternatives Inc. in the 1990s, and Edison Schools Inc. in the late 1990s and 2000s (pp. 8–9). They all attempted to improve K-12 education in the U.S. by using the commercial model. However, at no time in the past forty years has a for-profit model in education been able to improve student outcomes and make money simultaneously. More often than not, they even fail to raise student performance.

Abrams (2016) claimed that the main reason why there is a market failure when the corporate model is applied in education, as well as in healthcare and prisons, is because the standard business relationship does not function normally. To make this point, Abrams references an article from 1980 by a Yale law professor named Henry Hansmann:

Hansmann argued that schools, nursing homes, hospitals, and relief agencies…do not fit the commercial model because of a particular type of ‘market failure.’ In the case of schools and relief agencies, the recipient is not the purchaser….[O]ne should be adverse, Hansmann wrote, to using a for-profit provider of schooling for one’s children because one would likewise be hard pressed to know if services have been provided as promised. (p. 175)

In other words, the customer is not really the customer when it comes to prisons, medical care, and education. In Michigan’s private prisons, the prisoners are not actually the customers. One could argue that the State of Michigan is essentially the customer here, and they actually have an incentive to cut costs by hiring the most inexpensive subcontractors. Patients in doctors’ offices are customers, but much of the time, insurance companies are paying. Who really is the customer in these situations?

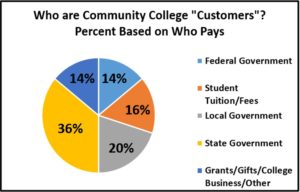

As an example in education, when a community college student begins attending courses, it is easy to assume she is the customer because she is paying to get an education. However, if we use the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics, then this student is only 16% customer because the tuition and fees in community colleges account for that percent in revenue (USDOE, 2015). The biggest customer is the state at 36%. The local government is about 20% customer, and the federal government is 14% customer. The rest comes from grants, gifts or donations, institutional revenues, etc. If all parties who pay are accounted for, then the student is actually one of the least important customers. However, Abrams (2016) calls the student the “immediate consumer” (p. 174). This makes sense because students are the face of higher education’s chain of customers, the ones who receive the service directly. They are also the ones who initiate a chain of higher education funding without which institutions could not exist.

What about the business community that is benefiting from local graduates? They must be customers as well because sometimes they determine a fair amount of what community colleges offer, especially for technical, trade, and health programs. They do not often “pay” for these graduates directly. However, they do set standards that colleges must adhere to in order to receive the benefits that these businesses may offer, such as grants or guaranteed employment, when they enter into apprenticeship agreements. We need to add them to the list of customers, too, after students, the state, the federal government, local taxpayers, and donors or donative resources.

More crucially, all these varying “customers” are not in a position to gauge whether they are getting their money’s worth from the education they are helping to pay for. As Abrams (2016) notes, there is an “information asymmetry” which does not allow customers in education to be able “to judge the quality of service rendered” (pp. 173-74). The same thing happens in healthcare. If a patient is the customer, and the doctor or hospital is the business, then should doctors automatically do what the patients want? Or are we supposed to trust the doctors and clinics to make important decisions about diagnoses and spending? Applying the commercial model to doctors and patients, just like colleges and students, sets up an information imbalance which can be taken advantage of. In fact, in a well-known article, Steven Brill from Time magazine exposed a common and disturbing hospital billing practice that hinges on information asymmetry.

When for-profit colleges focus solely on profits, and students are not able to judge whether these institutions are better or worse than others, then this mismatch of information can lead to abuse and poor outcomes that are not dissimilar to problems in private prisons and the healthcare system. For example, for-profits have much higher federal student loan defaults, mostly because graduates may not actually benefit from degrees from these institutions. For-profit graduation rates are usually much lower as well. Some for-profits have even been known to aggressively market to veterans, a practice that is highly unethical and in some cases illegal. The U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) has been cracking down on these institutions recently, and it has shown that for-profits are far worse than community colleges regarding federal aid, but much damage has already been done.

Perhaps the most alarming aspect of the for-profit education industry, which numbers in the range of 1700 institutions, is that they market specifically to at-risk students. Surprisingly, these students are more apt to be unemployed and make less money after attending a for-profit college. One can read a good study about these findings here or a shorter overview of the study here. The reason why this happens is because due to unfair advertisements, students are unable to discern the difference between the quality of a degree from a local for-profit university compared to a local state college. For-profit colleges use misleading advertising, often making wonderful and alluring promises to potential students, which are difficult to distinguish from the real-world benefits of having a degree from an accredited institution of higher education. Thus minorities and the poor, the very people who might benefit most from postsecondary education, are also the ones who are often conned and fall victim to for-profit target marketing. Sadly, many for-profit companies target minorities because they will be able to qualify for the most student aid offered by the government.

Other unintended consequences arise from using the business model in higher education. For example, for-profit corporations focus on a rigid decision-making hierarchy over shared governance. As Mark Burstein (2015), President of Lawrence University, noted in an article in The Chronicle, “Some business advisers, for example, believe that delegation through a hierarchical authority structure brings more rapid and efficient change than the shared-governance model many of our institutions rely on. But if we disenfranchise community members, we are likely to undermine the learning environments that are essential to our success” (para. 11). Equally problematic with this hierarchical decision-making approach is that it disenfranchises faculty and staff leaders at the very least, and at the very worst it instills fear. Faculty and staff are often the best resources for generating ideas to improve educational outcomes, retention, etc. Unfortunately, the CEO model does not leave much room for shared governance.

I attended a conference on higher education several years ago in which there was a session on how to increase the number of students at colleges and universities. In a room of well over 100 people in education, most of whom were administrators, no one batted an eye when the moderator made the assumption that students were customers. I raised my hand and asked, “Are we sure that students are in fact customers? Because the last time I checked, I didn’t need to take a test before I ordered a burger.” Everybody chuckled, and then the president of a university spoke up and said something to the effect of, “That’s a fair point. However, students are customers because we rely on them for a great deal of revenue.” The case was closed, and everyone moved on with the discussion about how to attract more customers.

The use of the term customers for students, couched in the overall corporatization of higher education, is increasing in institutions across the nation, especially in light of recent political changes. Even nonprofits are facing the stark reality of declining enrollments and are being forced to think about alternative sources of funding. Of course, not all institutions of higher education are resorting to the CEO-based commercial model to solve their funding problems. However, there is a pendulum swing happening all over, and unfortunately, many college presidents and boards are making choices that move toward the for-profit business model. They are sometimes subtle changes, such as the type of marketing employed or the number of dual-enrolled students taught by college instructors on high school campuses, but they are definite nonetheless. It is a term that changes how we view higher education as a whole. The more an institution views students as customers, the more that institution will adopt a for-profit mindset.

An even more subtle yet equally pernicious effect is how many institutions are now being managed internally. Increasingly, segments within institutions of higher education are being analyzed like a business would run internal productivity assessments. Administrators ask this question about specific areas and activities in colleges: “What is the ‘return on investment’ (ROI) for _____ in this institution?” It may be commonplace in the business world, but to dice up sections of an institution of higher education and calculate returns on investment is a practice not usually associated with education in general.

There is a precedent for this because economists at CAPSEE are asking questions such as, “What are the labor market outcomes (i.e., ROI, meaning earnings after college) for remedial English and math courses?” (Hodara & Xu, 2014). They claim to find increases in earnings for students who took remedial English, but decreases in earnings for remedial math takers. For college-level math students in two-year colleges, economists find no increase in earnings (Belfield, 2015). Their choice of statistical inquiry makes sense because many CCRC researchers are labor economists or economists who view college as a factory model. Conceptually and statistically, it seems near impossible to be able to attribute an increase or decrease in wages later in life to one or two sequential courses a student takes in college. However, applying an ROI-based mindset to any activity is what many economists are trained to do, and this mindset is now permeating all levels of higher education.

Case in point, if faculty wish to begin an initiative, they are often required to demonstrate that their program is self-sustaining before it is approved. Then they are provided temporary grant money, such as an “innovation grant,” but are subsequently required to make the initiative sustainable. “Sustainability” is the administration’s term for “an initiative must make enough money to cover its costs.” This means faculty are required to write a proposal that includes an ROI calculation. This business approach halts good ideas because most small initiatives cannot be shown to generate a direct return on investment. It also leads to more for-profit ideas, such as marketing shirts and other college products at local stores, overinvesting in website designs, and creating new student fees for educational interventions.

What presidents, policy advocates, and legislators do not appear to understand is that higher education itself is a direct money-losing enterprise. The entire goal of an institution of higher education is to invest a great deal of resources into students without any immediate return on that investment. Many studies have been published about the wonderfully high return on investment that education provides, but these returns go to society before they are funneled back to colleges and universities. Returns are often in such forms as lower crime, lower public expenditures—as in spending on welfare and healthcare—and higher tax revenue. A few of the numerous studies on higher education’s enormous ROI can be found here, here, here, and here.

In college, the ASAP program of the CUNY system in New York shows a return on investment of about 4 to 1 for taxpayers and 10 to 1 for students. That money does not come directly back to CUNY, however. It is funneled through higher taxes paid back to the community after graduates get jobs. In other words, the CUNY system spends about $5,000 per student per year over and above what the college, taxpayers, and students already pay for an education. In return, they more than double community college graduation rates. Again, however, the CUNY system does not see any of that money directly filling its bank accounts. In spite of this, CUNY’s leaders still understand it is a wise investment for their city, state, and country. Hardly any short-term, profit-based business person would recommend this amount of investment in students without a direct cash return. It just is not how society views education, or any enterprise, any longer.

As evidence of this, in a move contrary to the data, it appears our entire political system is headed in the direction of privatization in the realms of healthcare, the prison system, and education. In a New York Times article by Eduardo Porter, Professor of Economics Raymond Fisman summarizes the pervading for-profit frame of mind: “‘There’s a magical thinking among business executives that something about the profit motive makes everything run better….What is government going to be like when it is run by billionaire C.E.O.s that see the private sector as a solution to all the world’s problems?'” Porter continues, “A serious body of economics, not to mention reams of evidence from decades of privatizations around the world, suggests this belief is false” (para. 8-9).

If we truly believe in access, opportunity, and support for students entering colleges and universities, especially our most at-risk students, we may wish to oppose this movement toward corporatization. One way to do this is to make long-term return on investment arguments that may persuade administrators, presidents, boards, and faculty to invest more funds in students without a guaranteed ROI that goes directly back into college coffers. In other words, it should be acceptable if colleges spend more money on initiatives that improve outcomes even though they may not see any of that money return to their bottom line immediately. If public colleges are indeed still “public,” then using them as a means by which to improve society should be welcomed and supported.

Randal S. Franz, Professor of Management in the Schools of Business and Economics at Seattle Pacific University, would agree with this sentiment. After discussing the question of higher education’s clientele, Franz (1998) concluded, “Society is our customer” (p. 64). This makes sense because society pays taxes, which pay for federal, state, and local subsidies of higher education. Remember, however, society also benefits from higher education in the form of lower crime rates, higher tax bases, lower unemployment, and many other advantages that accompany a more highly educated population. We can indeed have it all—increased profits and high spending in education—but we do have to wait a while for that profit. Thus we need to recognize that education is a long-term investment which pays off greatly. We also need to keep investing in it, in all levels, and to invest thoughtfully.

References

Abrams, S. E. (2016). Education and the commercial mindset. Harvard University Press.

Bailey, T. R., Jaggars, S. S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: A clearer path to student success. Harvard Press.

Belfield, C. (2015). The labor market returns to math in community college: Evidence using the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 (A CAPSEE Working Paper). Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment, Teachers College, Columbia University. https://www.capseecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/labor-market-returns-math-community-college.pdf

Burstein, M. (2015, March 2). The unintended consequences of borrowing business tools to run a university. The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Unintended-Consequences-/190489/

Cunningham-Parmeter, K. (2011). Alien language: Immigration metaphors and the jurisprudence of otherness. Fordham Law Review, 79(4), 1545–1598. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol79/iss4/5/

Egan, P. (Michigan to clamp down on privatized prison deals.

Episode 521: The town that loves death.

Flaherty, C. (2016, April 11). Professor pay up 3.4%. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/04/11/annual-aaup-salary-survey-says-professor-pay-34

Franz , R. S. (1998). Whatever you do, don’t treat your students like customers! Journal of Management Education 22(1), 63–69. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/105256299802200105

Koch, J. V. (2018, January 9). No college kid needs a water park to study. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/09/opinion/trustees-tuition-lazy-rivers.html

Pew Charitable Trusts. (2015). Federal and state funding of higher education: A changing landscape. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/06/federal_state_funding_higher_education_final.pdf

Pew Charitable Trusts. (2019). Two decades of change in federal and state higher education funding. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2019/10/two-decades-of-change-in-federal-and-state-higher-education-funding

Porter, E. (2017, January 10). Prisons run by C.E.O.s? Privatization under Trump could carry a heavy price. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/10/business/economy/privatization-trump.html

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2009). Academic capitalism and the new economy. Johns Hopkins University Press. https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/academic-capitalism-and-new-economy

State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO). (2015). State higher education finance: Fiscal year 2015. https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/state-higher-ed-finance-fy2015.pdf

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2015). Table 333.10: Revenues of public degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by source of revenue and level of institution: 2007–08 through 2013–14. Author. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_333.10.asp

, September 16). Fancy dorms aren’t the main reason tuition is skyrocketing. Five Thirty Eight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/fancy-dorms-arent-the-main-reason-tuition-is-skyrocketing/