ADDSUP: A New Framework for Assessing Public 2-Year College Completion

Alexandros M. Goudas (Working Paper No. 17) March 2024

Overall postsecondary enrollment in the U.S. remained relatively low until after World War II (Heckman & LaFontaine, 2010). High school completion peaked nearly the same time and has remained consistently in the 80–90% range (McFarland et al., 2017). However, college attendance started rising significantly in the 1950s (Heckman & LaFontaine, 2010). Beginning in the early 1970s, the proportion of the population who have a 4-year college degree began to rise more rapidly, cresting recently at approximately one third of U.S. adults aged 25–64 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Broadening this definition to include any postsecondary degree attainment, the U.S. Department of Education (2020) found that by 2018, 47% of U.S. adults aged 25–64 had completed some type of postsecondary education. Viewed through a contextual and historical lens, U.S. postsecondary completion is at an all-time high.

Nevertheless, researchers have repeatedly highlighted that these rates have remained lower than they could be, and racial and socioeconomic inequities abound once the data are explored beyond superficial overall numbers (Belfield & Levin, 2007; Cahalan et al., 2017). As a result, in tandem with the rise in college completion beginning in the early 1970s, scholars and theoreticians initiated systematic and thorough explorations of research and data to investigate the reasons why college students drop out (Berger et al., 2012). Beginning with Spady’s (1970) foundational sociological research in higher education, Dropouts from Higher Education: An Interdisciplinary Review and Synthesis, several seminal theories of retention have been proposed and studied. Some of the most popular frameworks are Tinto’s Institutional Departure Model, Bean’s Student Attrition Model, Bean and Metzner’s Non-traditional Student Attrition Model, and Astin’s Student Involvement Theory (Aljohani, 2016).

In spite of the significant amount of research and modeling undergirding the most common theories of postsecondary retention and completion, many theoretical frameworks and their studies contain significant limitations. Meta-analyses of theoretical frameworks on student retention have concluded that much of the research used to support these theories is not generalizable (Aljohani, 2016; Manyanga et al., 2017). Moreover, the limited primary research that is included in some of the frameworks has relied on nonrepresentative samples from predominantly white 4-year institutions composed of mostly traditional-aged students.

Even scholars who helped create seminal theories have criticized their original research as lacking, especially regarding their practical applicability. For example, Tinto and Pusser (2006) concluded, “Despite years of effort and a good deal of research on student persistence, it is apparent that rates of college completion in the United States have not changed appreciably in the past 20 years” (p. 2). Furthermore, Tinto (2010), referring to persistently low college completion rates, stated, “It is clear that gains in our understanding of the process of student retention have not been translated into gains in rates of institutional completion” (p. 52). This may be due to a lack of reliable and representative data in these frameworks, as well as an overreliance on the idea that a lack of social integration causes much of attrition.

Overall, there are two significant issues with both current and past theories of college student retention and completion: First, they contain incomplete data and tracking of alternatives measures of success such as transfer rates, completion at other institutions, and job attainment. More importantly, they have excluded, and thus do not directly address, the tens of millions of public 2-year college students, particularly at-risk students, students of color, low-income students, part-time students, and those who have taken remediation and developmental education (R/DE).

To address these limitations, I propose a new framework that can be used to analyze 2-year public college retention and attainment: the ADDSUP model (Alternative Definitions and Designations of Success for the Underrepresented in the Postsecondary). Nearly 6 million students currently attend the approximately 1,500 2-year colleges across the nation (Hussar et al., 2020), and most of these students are considered at-risk and underprepared (Bailey et al., 2010). Furthermore, several recent and widespread reforms have changed the design and implementation of R/DE in a large number of institutions and state systems. Therefore, this paper also proposes a a new conceptual framework and its application in assessing current longitudinal public 2-year college education data and recent reforms, one that is more inclusive and representative of the actual student population attending community colleges in the U.S.

Background on Current Postsecondary Theoretical Frameworks

Modern theories on persistence and degree completion in higher education, while contributing to a general understanding of 4-year college student behavior, are predominantly influenced by outdated and incomplete research, in addition to other significant flaws and limitations. First, scholars place an excessive focus on the roles of social integration and student-institution interactions rather than more significant factors of student background, access to resources, and levels of support. Further, if any data undergird these theoretical frameworks, scholars have typically cited outdated studies; nonrepresentative samples; samples with predominantly white, affluent, and traditional-aged students; and incomplete datasets that do not reflect current postsecondary student demographics, especially at public 2-year colleges. Also, since the definitions of attrition, persistence, retention, and are so ill-defined in the literature, researchers have varied widely on what constitutes success or failure. Finally, if nontraditional students and the differing factors that cause their attrition are considered in the research, any focus on socioeconomic causes of attrition is lost in the laundry list of other contributing factors that are enumerated.

An Excessive and Misplaced Focus on the Theory of Social Integration

To understand current theories of attrition and completion and their flaws, one must delve into the most frequently cited foundational theories. For instance, Spady (1970, 1971) has been credited with being the first modern scholar to highlight the theoretical framework of college attrition (Aljohani, 2016; Berger et al., 2012). Though Tinto (1975) broadened the idea, Spady (1970, 1971) founded his theory on a framework to explain suicide. One could argue, therefore, that the seminal papers of the modern field of retention research contained deeply flawed and erroneous analogies, assumptions, and conclusions as applied to higher education, out of line with more recent research into the most critical factors affecting college enrollment, attrition, and attainment, all of which are more correlated with socioeconomic status (SES) (Cahalan et al., 2017). Aside from the foundation on suicide theory, Spady, Tinto, and Pascarella, arguably the three most influential seminal retention theorists, focused predominantly on student social interactions and “relied heavily on socialization or similar social process processes (e.g., shared values and friendship support) to explain the attrition process” (Bean & Metzner, 1985).

Though Spady (1970) and Tinto (1975) began with a hyper-focus on social integration and student feelings, both authors later honed their theories to include other sociological factors (Spady 1971; Tinto, 1987, 2010), including academic background, and to some degree, SES. Over recent decades, a slew of researchers contributed to and changed these theories to include many types of factors affecting attrition (Berger & Braxton, 1998; Berger et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the excessive focus on sociological factors of retention, especially the link to suicide, has skewed modern views on college retention and has shifted scholars’ views away from more relevant and powerful explanations of student departure, such as socioeconomic, racial, and equity-based causes.

Incomplete and Flawed Data Undergirding Seminal Theoretical Works

In addition to the skewed basis in suicide theory, the foundational pieces outlining these theoretical frameworks have been characterized by a lack of sound data. Seminal authors either conducted no underlying primary research or cited other research that contained little or no data, or they cited incomplete data and limited datasets. This has also contributed to a biased view of modern college attrition. Past researchers have relied heavily on theoretical conjecture and have overlooked and excluded detailed data on tracking student outcomes in terms of transfer, stopouts due to a lack of financial resources or to job attainment, or completion at institutions other than the first one at which students started. Much of these tracking limitations were a result of incomplete data due to the complex nature of student behavior and mobility, as well as a lack of any national systemic ability to track students. However, some theoreticians never attempted to elaborate their positions with data-driven arguments, and the focus of their articles could be characterized as overly theoretical and lacking in practical and in-depth application.

For instance, Spady (1971), used a sample of 683 first-year students at the University of Chicago who started college in 1965. Acknowledging and building on Spady, by contrast, Tinto (1975) provided a comprehensive but selective compilation of research into student attrition that existed prior to his article’s publication, yet he included no numerical or statistical analyses, nor any analysis of specific student-level causes of attrition. Bean (1980) reported the results of a survey of 366 male and 541 female first-year college composition students at a Midwestern 4-year university, all full-time and from a nonrepresentative sample. Astin (1984), like Tinto (1975), also compiled others’ research, but he included no cross-sectional or longitudinal data and relied heavily on theory and conjecture, which may have contributed to the overreliance on theories pertaining to social integration and a dearth of emphasis on socioeconomic factors.

More recent meta-analyses of the most common postsecondary theoretical frameworks have also highlighted these drawbacks and have argued that past theoreticians have differed in their definitions of attrition and retention. The newer scholarship has also highlighted the fact that the seminal authors have placed an overemphasis on homogenous and nonrepresentative student samples. First, because of a lack of clear definitions for attrition, persistence, and retention, scholars have not agreed to what constitutes the correct variables to be analyzed. Thus, research and findings have been in disarray. For example, Nicoletti (2019) noted the lack of specificity of definitions and data in the modeling of these theories: “Several dropout models tend to have a loose and general specification of both the involved variables and the processes that use these variables and that, usually, also determine the values associated with several of those variables” (p. 62). Manyanga et al. (2017), in line with Nicoletti (2019), argued that “the retention agenda is further complicated by the lack of uniform standards/metrics that define student success” (pp. 31–32).

In terms of past research and their nonrepresentative data, Aljohani (2016) found that “one of the most well-recognised limitations of the student retention studies concerns their generalizability. Most student retention studies are undertaken in particular institutions and their findings are usually not easily generalised to other institutions” (p. 12). More strikingly, Manyanga et al. (2017) stated, “It should be noted that most of the models of student attrition that were developed before 1990 contained some sweeping generalizations and lacked specific student demographic data” (p. 36). Therefore, most prior research into student attrition and its causes contains significant confounding factors due to a lack of consistent definitions and representative samples.

The Limited Focus on Socioeconomic Factors

Only a few seminal theoretical models have included a focus on socioeconomic factors and their effects on retention and completion. Bean and Metzner (1985), for instance, investigated the factors surrounding attrition and retention among nontraditional students in college. The authors characterized such practical inhibiting factors as child care and work as “environmental variables” and “background variables” (p. 492), and they suggested that when these variables are lacking, nontraditional students’ potential for leaving college rises. Bean and Metzner also considered such critical factors as age, full- and part-time status, high school performance, ethnicity, gender, and parental education levels. These aspects and their effects on college attrition had been largely ignored or minimized in prior literature.

However, in spite of the inclusion of these factors in this paper, the characterization of these students as “nontraditional” simply reinforces and reflects the hyper-focus on traditional students that the corpus of retention theory has had; the focus of modern theory has not shifted significantly to SES and related factors. For example, summaries of trends in retention theory still have a predominant focus on student interactions, commitment, motivation, and self-efficacy (Berger et al., 2012; Demetriou & Schmitz-Sciborski, 2012), all of which put the onus on the student or the institution to address social factors. However, currently there is a conspicuous lack of focus on SES, financial resources, background, race or other significant predictors of noncompletion (Cahalan et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2011).

A number of slightly more recent papers have focused more on these crucial issues, such as Levin and Levin’s (1991) paper entitled “A Critical Examination of Academic Retention Programs for At-Risk Minority College Students,” Braxton and Lee’s (2005) “Toward a Reliable Knowledge About College Student Departure,” and Tinto’s (2010) “From Theory to Action: Exploring the Institutional Conditions for Student Retention.” While these paper and other similar ones have begun to address more important aspects of the theoretical frameworks, such as SES, race and gender, and academic background, they still have not had the impact of shifting the general field of theory in retention and completion. These more recent papers could thus be termed spin-off research—papers that have attempted to move the field toward more pertinent and revelatory theories but have failed to make inroads into the general view of college retention that is overwhelmingly based on the narrow focus of student social interaction.

Foundational and Modern Theories Exclude At-Risk 2-Year College Student Data

Aside from a lack of data in general and the overuse of nonrepresentative samples when authors included statistical analyses, an equally important limitation in theories on retention and attainment lies with the prior exclusion of more comprehensive longitudinal completion data tracking higher numbers of students at increased numbers of institutions of higher education. This exclusion has omitted 2-year college student data in particular. These data have highlighted causes of at-risk student attrition that differ from 4-year students and exposed the traditional theories’ lack of attention to financial factors that predominate 2-year college student attrition, especially for those at-risk students who have participated in R/DE.

Until recently, little has been published on 2-year college tracking and completion, especially including critical data such as transfers to 4-year institutions, transfers to other 2-year colleges, part-time student data, data disaggregated by such metrics as Pell Grant status and varying time frames in which students are now tracked: 3-year, 6-year, and more recently, 8-year metrics. In fact, the most commonly cited databases in higher education, the U.S. Department of Education’s (USDOE) National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), failed to include part-time college student data in its IPEDS completion metrics until 2017 (Lederman, 2017). This is in spite of the fact that under half of all students at all types of colleges in the nation are exclusively full-time (Shapiro et al., 2018, p. 9).

Attempting to address the lack of precise data found in the USDOE’s NCES databases, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (NSCRC) is perhaps the most noteworthy research institution making strides in longitudinal student tracking to accurately reflect 2- and 4-year college attainment metrics. The NSCRC’s data comes from access to over 3,600 institutions’ data on enrollment, transfer, and completion, thus enabling researchers to track nearly 97% of all college enrollments across a variety of types of institutions, including 2- and 4-year public and private colleges, and include part-time, dual-enrolled, and nontraditional students (Shapiro et al., 2018, p. 31). Recent cohort-based reports have demonstrated that the 6-year graduation rate for 4-year public college students has risen to 67% (Shapiro et al., 2019b, p. 2). The 2-year college completion rate has peaked at over 41% after tracking students for 6 years (Shapiro et al., 2019b, p. 2), and the combined overall 6-year attainment rate for all students has risen to 66% (Shapiro et al., 2018, p. 10).

In a relatively new method for calculating community college completion, the NSCRC disaggregated attainment by tracking students who started at public 2-year colleges and then transferred and attained degrees at 4-year colleges and other 2-year institutions. Prior research typically assessed student completion only at the starting institution, which has resulted in an incomplete picture of attainment rates, such as the 27% graduation rate for students in the 2011 cohort who started and finished at the same public 2-year college (Shapiro et al., 2017, p. 25). However, if transfers to 4-year institutions are included, that rate increases to 34%; if transfers to other 2-year institutions are included, an analysis typically excluded in other data, then the total completion rate rises to 38%. Remarkably, in the first of this type of analysis to be conducted, the NSCRC extended the 2-year college student completion time frame from 6 years to 8 years to account for the fact that a majority of 2-year college students are part-time and thus take longer to finish college. In this innovative analysis, the total public 2-year college completion rate has peaked at 45% (Shapiro et al., 2019a, p. 3). Looking at 4-year public college student completion after 8 years using data from a 2013 incoming cohort, the NSCRC found that bachelor’s degree graduation rates rose to nearly 70% (Shapiro et al., 2019b, p. 4).

Almost none of these recent and revelatory data has been incorporated into the revision, creation, and promotion of existing or modern theories of postsecondary retention and completion. The nearly 6 million students currently attending 2-year colleges across the nation (Hussar et al., 2020) may thus be subjected to retention policies designed to affect mostly white, traditional-aged, 4-year college students due to retention and completion theories based largely on data, if present at all, which was generated from traditional universities from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Braxton and Lee (2005) noted that a significant amount of the prior research in Tinto and other frameworks should have been excluded due to problems with generalization, methodology, and findings. Even modern summaries of the evolution of retention theory have noted the singular focus on such ideas as student integration, self-efficacy, and motivation (Berger et al., 2012; Demetriou & Schmitz-Sciborski, 2012). This has exposed a yawning gap between the traditional and current foci of theories of retention and completion and a more modern understanding of most postsecondary students’ experiences, including SES, race, and student background, which collectively have a larger impact on student success in college than the aforementioned student integration factors (Cahalan et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2011).

Manyanga et al. (2017) summed up the vast difference between the traditional theories’ characterization of a typical student’s retention and completion and contrasted it with a more modern understanding of the complexity in defining and assessing attrition and success metrics:

The portrait of today’s student is fundamentally different from the past and continues to evolve. For instance, the prospective college graduate of today may have any of the following: several transcripts from multiple institutions that are later combined into a single degree transcript; complete alternative/specific courses to enhance workforce skills, rather than for graduating purposes. Some students enroll in college simply to “see how it feels” rather than having a graduation agenda; or take other classes online in addition to traditional face-to-face classes. Added to the mix are multiple degree transfer pathways, a relatively new academic avenue of advancement in the educational enterprise. (p. 32)

To make appropriate policies that effect positive change in the areas of attrition and attainment, it is critical to have the most accurate and in-depth information on student metrics. Only recently have institutions and policymakers had access to more accurate data. Unfortunately, the same attention that has been given to 4-year, traditional college students in the formation and execution of theories has not been provided to 2-year college students, of whom many, if not most, are at-risk students who are of low income, who are students of color, who are part-time, or who have taken R/DE coursework.

It is imperative that if institutions of higher education are attempting to increase access, retention, and completion rates for their most underserved populations, then policymakers will require a new framework of understanding how these students progress through college. This framework needs to include updated metrics, reliable longitudinal data, and several alternative definitions of success that can be applied to data on at-risk students beyond those which are commonly accepted in the retention literature. If recent reforms in community colleges and state systems are analyzed with this new framework, then a more comprehensive understanding of student success may emerge and change the future focus of reform in 2-year colleges.

ADDSUP: A More Inclusive and Representative Method for Assessing 2-Year College Completion

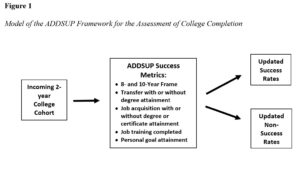

To address the dearth of theory and data in understanding how at-risk public 2-year college students progress and complete at various types of postsecondary institutions, I propose a new conceptual framework for analyzing success: the Alternative Definitions and Designations of Success for the Underrepresented in the Postsecondary (ADDSUP) model. In addition to proposing a revised and expanded scope of existing metrics, this model also recommends the inclusion of new and alternative definitions of success in 2-year college retention and completion. Once applied to existing tracking data and the most popular 2-year college reforms, this framework could change policymakers’ views on the success rates in institutions, states, and the nation, and it could redefine current theories’ beliefs on the causes of at-risk student attrition. Therefore, ADDSUP could alter policymakers’ future foci on the most effective types of reforms to implement. Figure 1 shows how an incoming 2-year college cohort could be analyzed using this alternative model for success.

Expanding the Time Frames of Existing 2-Year College Completion Metrics

The NSCRC is the leading research institution tracking nearly 97% of all individual postsecondary student enrollments through over 3,600 institutions of higher education (Shapiro et al., 2018, p. 31). This database has allowed researchers unprecedented access to the most holistic view of student enrollment, transfer, and completion to date. As an example of the power of this new access to previously inaccessible data, in the first of its kind, the NSCRC extended the typical 6-year time frame for public 2-year college completion to 8 years, and the result of the analysis demonstrated that students at these institutions graduated at a rate of over 45% as opposed to typically reported number of 39% (Shapiro et al., 2019a, p. 3). For 4-year public college students, the 6-year completion rate was nearly 63%; however, if the time frame is extended to 8 years, that rate increased to 69% (p. 3). Notably, after 8 years, 5.9 and 8.5% of public 4- and 2-year students respectively were still enrolled, according to this report (p. 5).

In addition to the innovative data on completion within extended time frames, the NSCRC has provided renewed attention to the data on 2-year college student enrollment intensity—i.e., exclusively full-time, exclusively part-time, and mixed enrollment—and an attention to these data is critical in understanding the changing definition of completion and its requisite time-frame analyses. For instance, nearly two-thirds of students attending public 2-year colleges were classified as mixed enrollees (Shapiro et al., 2017, p. 26), while just under 11% were considered exclusively part-time (p. 26). Therefore, an overwhelming majority, three fourths of all public 2-year college students, were part-time in enrollment intensity. Of the general population, at-risk students stand a higher chance of being part-time due to the increased burden of socioeconomic factors (Bailey et al., 2015).

Therefore, to account for the marked increase in completion rates when the time frame is extended to 8 years, and to account for the number of at-risk students whose enrollment intensity is exclusively part-time or mixed enrollment, the first component of ADDSUP is a change in the recommended time frame for the analysis of 2-year college completion to a minimum of 8 years. ADDSUP recommends a 10-year time frame should also be a new standard. This is critical because in order to be effective, frameworks for the correct understanding of completion metrics need to be data-driven and based in accurate information. Even if an eight- and ten-year completion rate of 45 to 50% is found, without expanding other definitions of success, that is markedly different than 39% and might alter policymakers’ choices when considering whether programs or institutions are effective and should be continued.

Tracking Transfers and Including Them as 2-Year Success Metrics

Typically, 2-year college completion success rates, as calculated by individual institutions, has only included students who start and complete any type of degree or certificate at the same institution. Recent longitudinal research has expanded analyses to include students who transfer to a 4-year or a different 2-year college and complete a degree or certificate elsewhere (Shapiro et al., 2017, 2018, 2019a, 2019b). Nearly half of all 4-year students attended a 2-year college in the decade prior to graduation (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2017). Since one of the traditional roles of public 2-year colleges has been to serve as starting points for 4-year graduates, the act of transferring should contribute to the success metric. Therefore, the second recommendation of the ADDSUP conceptual framework is that institutions and the USDOE should include students who transfer in their cohort success rates. The within-institution designation of success should not be limited to ultimate attainment at the institution to which the student transferred because transfer is one of the desired goals.

New Alternative Definitions and Designations of Success for At-Risk Students

In addition to the role of assisting student transfer to 4-year universities, public 2-year colleges also function as vehicles for job training. These institutions often create employment partnership agreements with local employers and serve as accredited training vehicles for students who wish to train and work locally (Carnevale et al., 2015). If a student’s goal is to attain work or reenter the job market after taking coursework at a college, and that student ultimately achieves gainful employment, regardless of degree or certificate attainment, then this should be considered a success in the institutional metric. Similarly, government unemployment insurance payments based on the Federal Unemployment Tax Act include 2-year college coursework as a component that satisfies federal requirements (College and University Professional Association, 2020). If the goal of the student is to fulfill workforce training while receiving unemployment insurance, and that goal was achieved without degree or certificate attainment, then that should be designated by institutions and databases as a success as well. Thus, the ADDSUP model includes job attainment and unemployment training completion as success metrics.

Nontraditional Student Goals Attained as a Success Metric

Aside from workforce training, community colleges have also served as a hub for community involvement in a small but not insignificant population of students, including retirees, lifelong learning participants, and people with disabilities (Van Noy & Heidkamp, 2013; Van Noy et al., 2013). These populations’ goals are typically not to earn credentials or complete degrees or certificates. Therefore, if students in these categories declare their intent as coursework only, and are included in a starting cohort at a 2-year college, the ADDSUP model would classify their outcomes as a success after the various time-frame analyses.

Applying the ADDSUP Conceptual Framework to Future Reforms

In 2015, 5 years after the initiation of Obama’s postsecondary completion agenda, research concluded that graduation rates had hardly changed (Field, 2015). In the 5 years since, rates have stagnated or marginally increased for those at 4-year institutions, and for students at 2-year colleges, 6-year completion rates have moved only a few percentage points higher (Causey et al., 2022; Shapiro et al., 2019b). The most recent NSCRC report, using a cohort that started college in 2016, has revealed only a slight increase in public 2-year college graduation rates compared to the prior few cohorts, ticking up to 43.1% (Causey et al., 2022). Part of the reason for this is that institutions and research organizations conduct incomplete analyses of data due to restricted and limited definitions of success, particularly for at-risk students who attend public 2-year colleges part-time. This is due in large part to outdated and flawed current theories on persistence and completion.

The ADDSUP model attempts to address incomplete and inaccurate modern theories of postsecondary persistence and attainment. Eight- and 10-year completion rate time frames should be the norm when analyzing public 2-year college success rates due to the fact that most students are part-time and the completion rate increases at least five percentage points when the time frame moves from 6 to 8 years. More importantly, students who obtain desired job attainment after training at a 2-year college should be included in the success category in the metrics. Transfers should also not count against an institution’s own success metrics. If unemployment insurance, entertainment, or lifelong learning were a student’s primary goals, and those goals were achieved, then that student’s success metric should be included in the outcomes.

One reason for the sweeping and potentially harmful reforms that started a decade ago was that community college success rates were deemed too low (Goudas & Boylan, 2012). The data researchers relied upon for this determination were incomplete. Employing the ADDSUP assessment model will produce more inclusive and accurate success data, highlight more important factors that contribute to this success, and alter the focus of future reforms to address the real barriers in postsecondary education, thus causing higher retention and completion.

References

Aljohani, O. (2016). A comprehensive review of the major studies and theoretical models of student retention in higher education. Higher Education Studies, 6(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/hes.v6n2p1

Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25(4), 297–308.

Bailey, T. R., Bashford, J., Boatman, A., Squires, J., Weiss, M., Doyle, W., Valentine, J. C., LaSota, R., Polanin, J. R., Spinney, E., Wilson, W., Yeide, M., & Young, S. H. (2016). Strategies for postsecondary students in developmental education – A practice guide for college and university administrators, advisors, and faculty. Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/PracticeGuide/wwc_dev_ed_112916.pdf

Bailey, T. R., Jaggars, S. S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: A clearer path to student success. Harvard Press.

Bean, J. (1980). Dropouts and turnover: The synthesis and test of a causal model of student attrition. Research in Higher Education, 12(2), 155–187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00976194

Bean, J., & Metzner, B. (1985). A conceptual model of non-traditional undergraduate student attrition. Review of educational research, 55(4), 485–540. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543055004485

Belfield, C. R., & Levin, H. M. (Eds.) (2007). The price we pay: Economic and social consequences of inadequate education. Brookings Institution Press.

Berger, J., & Braxton, J. (1998). Revising Tinto’s Interactionalist Theory of Student Departure through Theory Elaboration: Examining the role of organizational attributes in the persistence process. Research in Higher Education, 39(2), 103–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018760513769

Berger, J., Ramirez, G. B., & Lyon, S. (2012). Past to present: A historical look at retention. In A. Seidman (Ed.), College student retention: Formula for student success (pp. 7–34). Rowman & Littlefield.

Braxton, J. M., & Lee, S. D. (2005). Toward a reliable knowledge about college student departure. In A. Seidman (Ed.), College student retention: Formula for student success (pp. 107–127). Praeger.

Cahalan, M., Perna, L. W., Yamashita, M., Ruiz, R., & Franklin, K. (2017). Indicators of higher education equity in the United States: 2017 trend report. Pell Institute for the Study of Higher Education, Council for Education, Opportunity (COE) and Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy (AHEAD) of the University of Pennsylvania. http://pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Indicators_of_Higher_Education_Equity_in_the_US_2017_Historical_Trend_Report.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., Smith, N., Melton, M., & Price, E. W. (2015). Learning while earning: The new normal. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/Working-Learners-Report.pdf

Causey, J., Lee, S., Ryu, M., Scheetz, A., & Shapiro, D. (2022). Completing college: National and state report with longitudinal data dashboard on six- and eight-year completion rates (Signature Report 21). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Completions_Report_2022.pdf

College and University Professional Association for Human Resources. (2020, April 13). Student eligibility for unemployment benefits. https://www.cupahr.org/blog/student-eligibility-for-unemployment-benefits/

Demetriou, C., & Schmitz-Sciborski, A. (2012). Integration, motivation, strengths and optimism: Retention theories past, present and future. In R. Hayes (Ed.), Proceedings of the 7th National Symposium on Student Retention, 2011 (pp. 300–312). The University of Oklahoma. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364309350_Integration_Motivation_Strengths_and_Optimism_Retention_Theories_Past_Present_and_Future_Integration_Motivation_Strengths_and_Optimism_Retention_Theories_Past_Present_and_Future

Field, K. (2015, January 20). 6 years in and 6 to go, only modest progress on Obama’s college completion goal. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/6-Years-in6-to-Go-Only/151303

Goudas, A. M., & Boylan, H. R. (2012). Addressing flawed research in developmental education. Journal of Developmental Education, 36(1), 2–13.

Heckman, J. J., & LaFontaine, P. A. (2010). The American high school graduation rate: Trends and levels. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(2). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2900934/pdf/nihms-117813.pdf

Hussar, B., Zhang, J., Hein, S., Wang, K., Roberts, A., Cui, J., Smith, M., Bullock Mann, F., Barmer, A., & Dilig, R. (2020). The Condition of Education 2020 (NCES 2020-144). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020144

Johnson, J., Rochkind, J., Ott, A. N., & DuPont, S. (2011). With their whole lives ahead of them: Myths and realities about why so many students fail to finish college. Public Agenda. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507432.pdf

Lederman, D. (2017, October 12). The new, improved IPEDS. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/10/12/new-federal-higher-ed-outcome-measures-count-part-time-adult-students

Levin, M. E., & Levin, J. R. (1991). A critical examination of academic retention programs for at-risk minority college students. Journal of College Student Development, 32, 323–334. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ432314

Manyanga, F., Sithole, A., & Hanson, S. M. (2017). Comparison of student retention models in undergraduate education from the past eight decades. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 7(Spring), 29–41. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1188373.pdf

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., de Brey, C., Snyder, T., Wang, X., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Gebrekristos, S., Zhang, J., Rathbun, A., Barmer, A., Bullock Mann, F., & Hinz, S. (2017). The condition of education 2017 (NCES 2017–144). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017144.pdf

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2017). Contribution of public 2-year institutions to bachelor’s completions at 4-year institutions (Snapshot Report 26). https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SnapshotReport26.pdf

Nicoletti, M. (2019). 2016). Revisiting the Tinto’s theoretical dropout model. Higher Education Studies, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v9n3p52

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P. K., Bhimdiwali, A., & Wilson, S. E. (2018). Completing college: A national view of student completion rates – fall 2012 cohort (Signature Report No. 16). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport16.pdf

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P. K., Bhimdiwala, A., & Wilson, S. E. (2019a). Completing college: Eight year completion outcomes for the fall 2010 cohort (Signature Report No. 12c). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/NSC_Signature-Report_12_Update.pdf

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P. K., Yuan, X., Nathan, A., & Bhimdiwali, A. (2017). Completing college: A national view of student completion rates – fall 2011 cohort (Signature Report No. 14). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport14_Final.pdf

Shapiro, D., Ryu, M., Huie, F., Liu, Q., & Zheng, Y. (2019b). Completing college 2019 national report (Signature Report 18). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Completions_Report_2019.pdf

Spady, W. (1970). Dropouts from higher education: An interdisciplinary review and synthesis. Interchange, 1(1), 64–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02214313

Spady, W. (1971). Dropouts from higher education: Toward an empirical model. Interchange, 2(3), 38–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02282469

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of educational research, 45(1), 89–125. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543045001089

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (2010). From theory to action: Exploring the institutional conditions for student retention. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (pp. 51–89). https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-90-481-8598-6_2

Tinto, V., & Pusser, B. (2006). Moving from theory to action: Building a model of institutional action for student success. National Postsecondary Education Cooperative, Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/npec/pdf/Tinto_Pusser_Report.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017, March 30). Highest educational levels reached by adults in the U.S. since 1940 (Release Number: CB17-51). https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-51.html

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). International educational attainment. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cac.asp

Van Noy, M., & Heidkamp, M. (2013). Working for adults: State policies and community college practices to better serve adult learners at community colleges during the Great Recession and beyond. National Technical Assistance and Research Center to Promote Leadership for Increasing Employment and Economic Independence of Adults with Disabilities. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/odep/pdf/workingforadults.pdf

Van Noy, M., Heidkamp, M., & Kaltz, C. (2013). How are community colleges serving the needs of older students with disabilities? National Technical Assistance and Research Center to Promote Leadership for Increasing Employment and Economic Independence of Adults with Disabilities. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/odep/pdf/communitycollegesolderstudents.pdf